The key points

- ✓Urgency and frequency are real medical problems—even if you don't leak urine. You deserve treatment.

- ✓Pelvic floor physiotherapy is recommended by all major guidelines as a first-line treatment—before medication.

- ✓It's much more than "Kegels". A specialist assesses whether your muscles are too tight, too weak, or uncoordinated—and treats accordingly.

- ✓Half of people do pelvic floor exercises incorrectly after verbal instructions alone. Some techniques can make symptoms worse.

- ✓This is a low-risk treatment that addresses the cause, not just the symptoms—unlike lifelong medication.

Why I wrote this guide

I recently had a conversation with a patient who was confused and frustrated. She'd been experiencing urinary urgency and frequency for over 18 months. She was waking almost every hour at night, struggling to concentrate at work, and feeling embarrassed in meetings. Despite multiple investigations, she felt no closer to a solution.

When I recommended pelvic floor physiotherapy, she pushed back—quite reasonably. "Everything I've read online says pelvic floor physio is for incontinence," she told me. "I don't leak. I just need to pee constantly. How is strengthening a muscle going to stop me needing to go?"

It was a fair question, and it highlighted a widespread misunderstanding. So I promised to send her something that explains the science in plain terms. This guide is that promise fulfilled—and I'm publishing it because I know she's not alone.

What are urgency and frequency?

Let me start with definitions, because words matter—especially when they shape how seriously people take your symptoms.

Urgency is a sudden, compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to put off. It describes a sensation—the urge itself. Crucially, you may still be able to hold on. But the feeling is intense and distracting.

- Sudden, urgent desire to void that is difficult to postpone

- Typically accompanied by frequency (more than 8 voids per day or 2+ at night)

- Person usually CAN hold urine if they try (continence is maintained)

- Urgency may or may not be related to bladder fullness volume

- Urgency is subjective—the person experiences and reports the sensation

Important: The ability to hold urine does NOT mean the treatment is wrong or unnecessary. Urgency is distressing and life-altering even without incontinence.

Frequency means needing to void more often than normal. Most people pass urine 6–8 times during waking hours. Going more than 8 times, or waking more than twice at night, is considered increased frequency.

Incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine—actual leakage.

These are three distinct things. Many people have urgency and high frequency without ever leaking. They are not "incontinent," yet the constant feeling of needing to pee can be just as disruptive to work, sleep, and relationships.

Definition: Involuntary leakage with physical activity (coughing, sneezing, exercise, heavy lifting).

Mechanism: Pelvic floor muscles or urethral sphincter insufficiency means the sphincter cannot generate enough pressure to counteract the sudden intra-abdominal pressure increase.

Common in: Women after childbirth, post-menopausal individuals, people with connective tissue laxity.

Treatment response to pelvic floor physio: Often good; pelvic floor strengthening and neuromuscular re-education can improve sphincter support and reflex contraction.

Definition: Involuntary leakage preceded by sudden urge to void, often associated with high frequency and nocturia.

Mechanism: Detrusor overactivity (involuntary bladder muscle contractions) and/or severe sensory urgency leading to large volume leakage before person can reach toilet.

Key distinction: This does involve incontinence, whereas urgency alone may not.

Treatment response to pelvic floor physio: Often helpful as part of multimodal approach; pelvic floor relaxation can reduce urgency sensations; biofeedback and retraining enhance control.

Definition: Both stress and urgency incontinence present simultaneously.

Mechanism: Combined pelvic floor weakness and overactive bladder or sensory dysfunction.

Treatment: Often requires combination approach addressing both components.

Overflow incontinence: Leakage due to incomplete emptying; bladder remains overdistended.

Functional incontinence: Person has intact bladder and sphincter function but cannot reach toilet due to mobility, cognitive, or environmental factors.

Neurogenic bladder: Loss of normal nerve control due to spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, or other neurological conditions.

Your bladder is a sophisticated sensory organ. As it fills, stretch receptors in the bladder wall send signals through your nerves to your brain. Normally, the first sensation of filling occurs at about 40% capacity, with a stronger urge appearing closer to 90%.

In some people, these sensory pathways become hypersensitive. The nerves signal "full" at much lower volumes. Research suggests this may involve C-fibre nerves—normally silent receptors that only respond to noxious stimuli—becoming active during normal filling. This puts your early warning system on high alert.

The result? You can hold on, but it feels urgent. And because the signal keeps firing, you feel you need to go again and again. This is a physiological change in nerve signalling—it is not "in your head," though stress and poor sleep can amplify the sensation.

Source: Abrams P, et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 2002.

How is the pelvic floor involved?

The pelvic floor is a group of muscles that form a sling at the base of your pelvis, supporting your bladder, bowel, and (in women) the uterus. These muscles and your bladder work as a coordinated system.

There are two main problems that can occur:

1. The pelvic floor is too tight (hypertonic)

If your pelvic floor muscles are in a constant state of tension, they compress the bladder and limit its ability to stretch comfortably. This can make the bladder feel full at lower volumes—triggering that urgent sensation. It can also send confusing sensory signals that make the bladder "jumpy."

2. The pelvic floor is too weak or uncoordinated

If the muscles are weak or don't coordinate properly, you may struggle to suppress the urge when it arrives, or feel less confident about your ability to hold on during pressure spikes (like coughing or sneezing).

Here's the critical point: these two problems require opposite treatments. A tight pelvic floor needs relaxation. A weak pelvic floor needs strengthening. Doing the wrong exercises can make symptoms worse.

What the research shows

Research estimates that about 1 in 10 women have hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction. Among women with chronic pelvic pain, the proportion with tight, overactive pelvic floors rises to 60–90%. For these patients, strengthening exercises are contraindicated.

Source: Faubion et al., Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2012

What pelvic floor physiotherapy actually involves

This is not about doing Kegels from a YouTube video. Modern pelvic floor physiotherapy is a thorough, individualised process that often includes:

Assessment: A detailed review of your symptoms, a bladder diary, and often an internal examination to assess whether your muscles are overactive, weak, or uncoordinated. This is essential—without it, you can't know which treatment is appropriate.

Biofeedback: Using sensors or real-time ultrasound to help you see and understand what your pelvic floor is doing. Many people have no idea whether they're contracting or relaxing correctly. Biofeedback gives you visual feedback so you can learn.

Relaxation and manual therapy: If your muscles are too tight, the physiotherapist may use breathing techniques, stretching, and myofascial release to help them let go.

Bladder retraining: Gradually increasing the time between voids, teaching your bladder to tolerate normal filling without sending premature urge signals.

Targeted strengthening: Only if weakness is the problem. This involves structured exercises for both fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibres, supervised over time.

Lifestyle coaching: Optimising fluid intake, identifying irritants like caffeine, addressing constipation, and improving sleep hygiene.

A typical programme lasts at least 3 months with regular follow-up. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) specifically recommends supervised programmes over written handouts alone.

There's a well-established spinal mechanism called the "guarding reflex." When you voluntarily contract your pelvic floor, it sends signals through the spinal cord that inhibit bladder contraction and reduce the urge sensation.

A study by Shafik and Shafik (2003) demonstrated this elegantly: voluntary pelvic floor contraction reduced bladder pressure from 28 cm H₂O to just 11 cm H₂O, while increasing urethral pressure—effectively suppressing the micturition reflex.

More recent research by Lucio et al. (2018) found that pelvic floor muscle contraction completely eliminated involuntary bladder contractions in 47% of women with overactive bladder, with significant reductions in the rest.

This is why learning to contract correctly—at the right moment, with the right technique—can genuinely reduce urgency. But it requires proper training.

Assessment and Diagnosis

What happens: The pelvic floor physiotherapist performs a detailed evaluation including:

- Detailed symptom history (onset, triggers, impact on quality of life)

- Bladder diary analysis (volume voided, frequency patterns, urgency triggers)

- Internal palpation assessment (internal vaginal or rectal examination to assess muscle tone, strength, endurance, coordination, and pain)

- Functional testing (ability to contract, relax, maintain sustained contraction)

- Identification of pelvic floor dysfunction pattern (hypertonicity vs. weakness vs. incoordination)

Why it matters: NOT all pelvic floor dysfunction is weakness. Some people have excessive tension restricting bladder capacity and triggering urgency. Treating tension with strengthening exercises makes it worse. Proper assessment ensures matched treatment.

Biofeedback and Proprioceptive Training

What happens: The physiotherapist uses real-time feedback (often using external ultrasound, electromyography, or manometry) to help you understand where your pelvic floor is and how to control it.

Why it works: Many people have lost proprioceptive awareness of their pelvic floor. They cannot feel the difference between contraction and relaxation. Biofeedback re-educates this awareness, which is the foundation for any functional improvement.

Evidence: Biofeedback significantly enhances outcomes in pelvic floor rehabilitation compared to exercise instruction alone.

Relaxation Technique and Tension Release

What happens: If excessive pelvic floor tension is identified, the physiotherapist teaches and performs:

- Deep abdominal breathing and coordination with pelvic floor relaxation

- Visualization and mindfulness techniques

- Soft tissue manual therapy (gentle stretching, trigger point release)

- Myofascial release techniques

- Education on posture and positioning to reduce unnecessary tension

Why it matters: This is where many DIY approaches fail. Excessive tension cannot be resolved by YouTube Kegel exercises. It requires skilled manual therapy and re-education.

Lifestyle and Bladder Retraining

What happens: The physiotherapist works with you on:

- Fluid intake patterns: Reviewing what you drink, when, and how much. Not restricting fluid (which is harmful) but optimizing intake

- Bladder retraining: Gradually extending time between voids if frequency is driven by habit rather than true need. This is done gradually and safely

- Caffeine, alcohol, and dietary triggers: Understanding which substances affect your symptoms

- Bowel management: Addressing constipation if present, as it exacerbates pelvic floor dysfunction

- Sleep and anxiety patterns: Understanding the bidirectional relationship between sleep disruption, anxiety, and urgency/frequency

- Activity modification: How to manage symptoms during daily activities and work

Evidence: Behavioral modification alongside pelvic floor physio improves outcomes significantly compared to either alone.

Targeted Muscle Training (when appropriate)

What happens: ONLY if weakness is identified, the physiotherapist prescribes specific targeted exercises:

- Exercises matched to your specific dysfunction (not generic "Kegels")

- Progressive resistance training with proper form

- Fast-twitch fiber training (quick contractions for reflex responses)

- Slow-twitch fiber training (sustained contractions for tonic support)

- Sport-specific or activity-specific retraining

Key point: This component is NOT the foundation; it is part of a comprehensive approach and only used when indicated by assessment findings.

Education and Long Term Management

What happens: The physiotherapist provides education on:

- What pelvic floor dysfunction is and how it affects your symptoms

- Why certain treatments are recommended for your specific presentation

- Strategies for maintaining improvements long-term

- Recognition of symptom triggers and preventative approaches

- When to seek additional specialist input (urology, gynecology, psychology, sleep medicine)

Why it matters: This education empowers you to be an active participant in your recovery, not passive recipient of treatment.

Why you can't just learn this from YouTube

Here's a statistic that might surprise you: only about half of women perform a correct pelvic floor contraction after verbal instruction alone.

In a foundational study by Bump et al. (1991), researchers gave 47 women standard verbal instructions on how to do pelvic floor exercises. The results were sobering:

- 49% achieved a correct contraction

- 25% used a technique that could promote incontinence (bearing down instead of lifting)

- 26% had ineffective or indeterminate contractions

Subsequent research has confirmed these findings. Among women who already have pelvic floor dysfunction, the proportion who contract incorrectly can be as high as 70%.

This is why professional assessment matters. A physiotherapist can identify whether you're contracting correctly, whether your muscles need strengthening or relaxation, and tailor a programme to your specific needs.

From the research

"Pelvic floor muscle training should not be implemented without an appropriate evaluation and adequate patient training. Providing the patient with verbal instructions and written handouts alone does not constitute evidence-based pelvic floor muscle training."

— College of Physiotherapists of Alberta, Clinical Practice Guidance

What the international guidelines recommend

I sometimes encounter scepticism about pelvic floor physiotherapy—from patients and even from other healthcare professionals. So let me be clear about what the evidence says.

Every major international guideline body recommends behavioural therapies (including pelvic floor physiotherapy and bladder training) as first-line treatment for overactive bladder symptoms—including urgency and frequency without incontinence:

- European Association of Urology (EAU): Strong recommendation for bladder training as first-line therapy, with Level 1b evidence that pelvic floor muscle training may improve frequency symptoms.

- NICE (UK): Recommends supervised bladder retraining combined with pelvic floor muscle training for women with frequency, urgency, or mixed incontinence—minimum 3 months duration.

- American Urological Association (AUA): Grade A (strong evidence) recommendation for bladder training for all OAB patients.

- International Urogynecological Association (IUGA): Describes pelvic floor muscle training as "a mainstay of behavioural treatment for overactive bladder symptoms."

These guidelines specifically include "OAB dry"—overactive bladder without incontinence. You do not need to leak to qualify for treatment.

What Does the Research Show?

For Stress Incontinence:

- Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is recommended as first-line treatment by NICE, ICS, and AUA guidelines

- Meta-analyses show 50-80% improvement or resolution of symptoms with structured PFMT

- PFMT is more effective than surgery alone when performed preoperatively, improving perioperative outcomes

For Overactive Bladder/Urgency:

- Pelvic floor physiotherapy combined with behavioral modification shows 40-50% reduction in urgency symptoms in clinical trials

- Effects are improved when combined with medication (anticholinergics or beta-3 agonists like Mirabegron) in multimodal approach

- NICE guidelines recommend PFMT as adjunctive treatment alongside or before medication

For Pelvic Pain/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome:

- Pelvic floor physical therapy has strong evidence for myofascial pain syndrome, prostatitis, and vaginismus

- Addressing pelvic floor tension often reduces pain significantly

Mechanism of Action in Urgency:

Pelvic floor physiotherapy appears to work through multiple mechanisms:

- Sensory modulation: Reducing pelvic floor tension can decrease sensory urgency signals

- Improved compliance: Relaxed pelvic floor allows bladder to fill to normal capacity before signaling need to void

- Reflex enhancement: Trained pelvic floor can generate faster reflex contraction during pressure spikes, enhancing continence

- Neuroplasticity: Biofeedback and retraining help rewire central nervous system responses to bladder filling cues

.

I want to be honest about this, because I believe in informed consent.

The strongest evidence for pelvic floor muscle training comes from studies on stress urinary incontinence. A Cochrane review (Dumoulin et al., 2018) of 31 trials found that women doing pelvic floor training were 8 times more likely to report cure compared to no treatment—56% vs 6%. This is high-quality evidence.

The evidence specifically for urgency and frequency without incontinence is more limited. There are fewer trials, and they show more variable results. A systematic review by Bø et al. (2020) found that 5 of 11 trials showed significant symptom reduction, but the studies were too different to combine statistically.

However, the rationale for recommending behavioural therapy first is not just about cure rates. It's about the risk–benefit balance. These treatments have essentially no side effects, low cost, and address underlying mechanisms rather than masking symptoms. If they work, you've solved the problem. If they don't work fully, medication can still be added.

Common myths—and the facts

Click each myth to reveal what the evidence actually shows.

The evidence

All major guidelines specifically include "OAB dry" (urgency without incontinence) as an indication for pelvic floor physiotherapy. The International Urogynecological Association describes it as "a mainstay of behavioural treatment for overactive bladder symptoms, such as urgency"—not just incontinence. I also refer men for chronic pelvic pain, prostatitis, and premature ejaculation.

Source: IUGA/ICS Joint Report on Conservative Management, 2017

The evidence

Research shows only 49% of women achieve a correct contraction after verbal instruction alone. A quarter use a technique that could worsen symptoms (bearing down instead of lifting). Without assessment, you don't know if your problem is tightness (needing relaxation) or weakness (needing strengthening)—and the wrong approach makes things worse.

Source: Bump et al., American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1991

The evidence

Research from the NOBLE study found that urgency—the sensation itself—accounts for the greatest reduction in quality of life among all OAB symptoms, greater even than incontinence. Sleep disruption from frequency affects work productivity, increases fall and fracture risk, and is associated with depression and cognitive decline. These are real medical consequences.

Source: Coyne et al., BJU International, 2004

The evidence

Restricting fluids concentrates your urine, which can irritate the bladder and worsen urgency. The Nurses' Health Study (65,167 women) found no benefit to fluid restriction for preventing incontinence. Current guidance recommends 1.5–2 litres per day—enough to stay hydrated without excess. What you drink (reducing caffeine) and when you drink (avoiding fluids 2–3 hours before bed) matters more than total amount.

Source: Townsend et al., Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2011

The evidence

Sensory urgency is a physiological problem involving nerve signalling and muscle coordination. While anxiety and poor sleep can amplify the sensation, research shows that urgency involves measurable changes in bladder sensory thresholds and pelvic floor function. Interestingly, studies also show elevated anxiety in "dry" OAB (without incontinence) compared to controls—suggesting urgency causes anxiety, not the other way around.

Source: Reynolds et al., Current Urology Reports, 2016

The evidence

Pelvic floor dysfunction is highly individual. Your friend may have had weak muscles needing strengthening; you may have tight muscles needing relaxation. What worked for someone after childbirth may be completely wrong for someone with sensory urgency. This is precisely why professional assessment is essential—generic advice can genuinely harm.

The burden of urgency—and why shame delays treatment

I want to acknowledge something that often goes unspoken: urinary symptoms carry a heavy burden of shame.

Qualitative research on patients with overactive bladder reveals common themes: isolation, reluctance to discuss symptoms even with close friends, perception of self-control failure, and associated guilt. As one patient in a study put it: "Women don't share this problem, even with other women."

Studies show that 48% of OAB patients report anxiety symptoms, and up to 30–50% report depression symptoms. Patients wait an average of 3.5 years between symptom onset and seeking help. That's years of unnecessary suffering.

I want to break that cycle. Urgency and frequency are common—up to a third of adults will experience overactive bladder symptoms in their lifetime. They are medical conditions, not personal failings. Seeking help is a sign of strength.

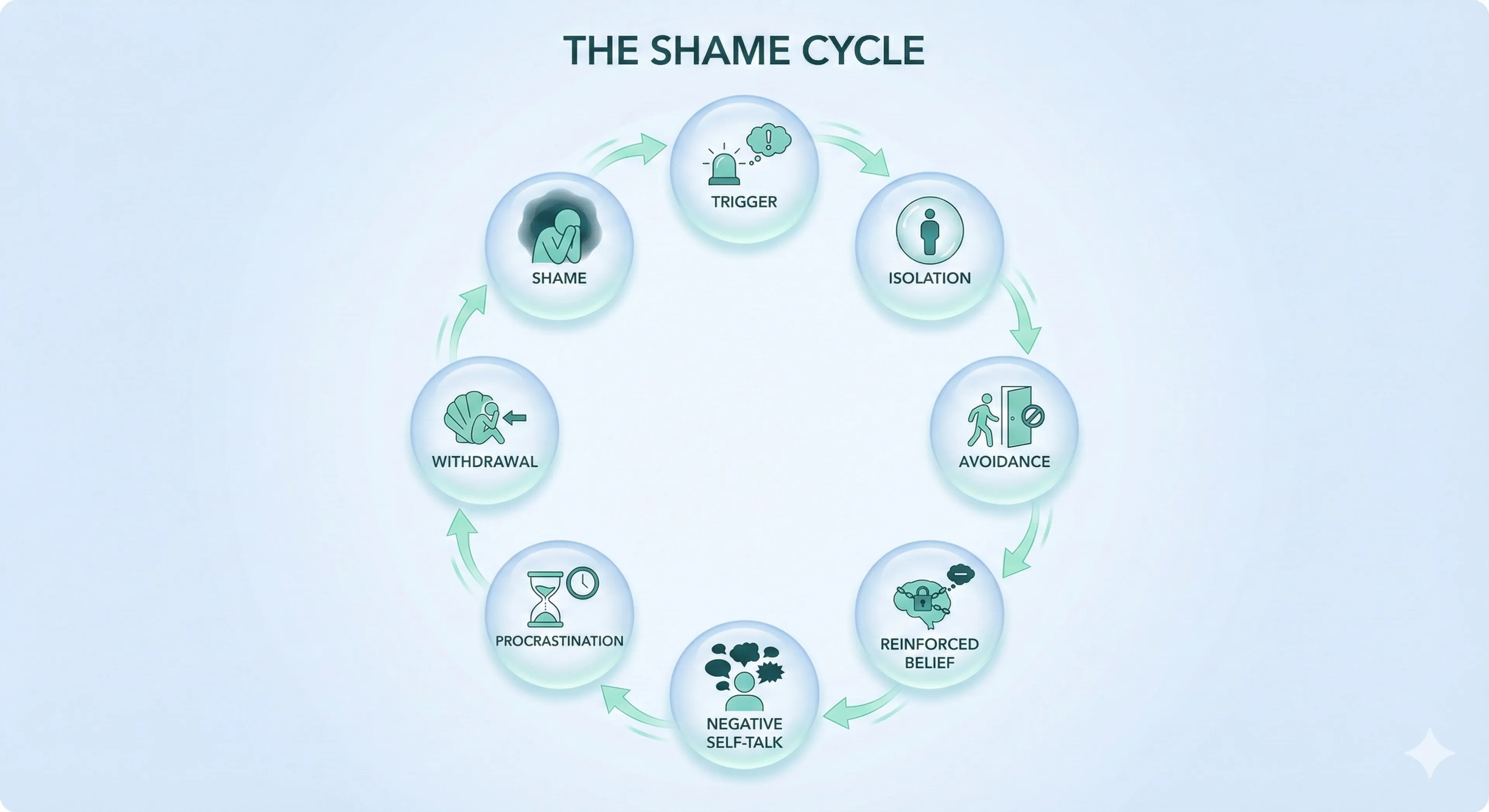

Misinformation does not only spread incorrect facts. It actively shapes how people understand their urinary symptoms, often creating shame before they ever speak to a healthcare professional. For many patients, the emotional burden begins not in the bladder, but in the information ecosystem they encounter when they search for answers.

Shame and misinformation reinforce one another in a loop that keeps people away from effective, guideline-based treatment.

The Shame Cycle

- A person experiences urinary urgency or frequency.

- They search online for explanations.

- They find misleading or conflated information linking urgency to incontinence.

- They assume the worst and feel ashamed or “broken.”

- They keep symptoms private and avoid seeking medical help.

- Symptoms persist or worsen.

- Shame deepens and becomes internalised.

- They may never access appropriate treatment such as pelvic floor physiotherapy or bladder retraining.

This cycle causes harm long before a patient is assessed in clinic.

What Research Shows About Stigma and Urinary Symptoms

The Impact of Shame on Health Outcomes

Patients with overactive bladder symptoms—even without incontinence—report quality-of-life impairment similar to those living with major depressive disorder or chronic pain.

Despite this, fewer seek treatment, largely because of internalised shame and fear of judgement.

Shame directly affects sleep, workplace performance, concentration, intimacy, and emotional wellbeing.

Treatment-Seeking Delays

Stigma and shame are major barriers to accessing care. Many individuals:

- plan their day around toilet availability,

- reduce social and travel activities,

- restrict fluids excessively,

- alter work routines to avoid embarrassment,

long before they consider speaking to a doctor.

By the time help is eventually sought, symptoms may have become chronic and psychological burden significant.

H4 — The “Invisibility” Problem

Urinary symptoms are not outwardly visible, yet people often experience intense internal anxiety about them. Many overestimate how much others notice their toilet habits.

This mismatch creates disproportionate fear, leading to social withdrawal and avoidance behaviours.

Gender Differences in Stigma

While stigma affects everyone, the form it takes often differs:

- Women may fear being seen as less feminine, sexually undesirable, or “not in control.”

- Men often interpret urinary symptoms as a loss of strength, autonomy, or masculinity.

Both narratives reinforce silence and delay access to effective treatment.

Key Insight:

Shame does not reflect the severity of the symptoms.

Shame reflects the quality of information people access.

Accurate, compassionate education dissolves shame; misinformation amplifies it.

Frequently asked question

Your first appointment typically lasts 45–60 minutes. The physiotherapist will take a detailed history of your symptoms, lifestyle, and goals. They'll explain the assessment process and ask for your consent before any examination.

An internal examination (vaginal or rectal) is often recommended to assess muscle tension, strength, and coordination directly. This is done with sensitivity and you can decline. External assessment using ultrasound is an alternative in some cases.

Based on the findings, they'll create an individualised treatment plan which may include manual therapy, biofeedback, bladder retraining, and home exercises. Follow-up appointments are usually every 2–4 weeks over at least 3 months.

Most people notice some improvement within 4–6 weeks, with continued progress over 3–6 months. Guidelines recommend a minimum of 3 months of supervised treatment before considering other options.

Results vary depending on the underlying cause, severity, and how consistently you do home exercises. Complete resolution isn't guaranteed, but significant improvement is common—studies show 50–80% symptom reduction in many patients.

Yes, pelvic floor physiotherapy is available on the NHS, though waiting times vary by area. Your GP can refer you, or in some areas you can self-refer to women's health physiotherapy services.

Private physiotherapy offers shorter waiting times and often longer appointment slots. I can provide referrals to specialist pelvic floor physiotherapists I work with regularly.

Absolutely not. Men have pelvic floor muscles too, and they can develop dysfunction. I refer men for pelvic floor physiotherapy for chronic prostatitis, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, post-prostatectomy incontinence, urinary urgency and frequency, erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation.

The principles are the same: assessment first, then targeted treatment based on findings.

If you've completed a supervised programme and symptoms persist, we have other options. Medication (Mirabegron or anticholinergics) can be added alongside continued behavioural strategies. For more severe cases, bladder Botox injections, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), or sacral neuromodulation may be considered.

The important thing is that trying physiotherapy first doesn't close any doors. It gives you the best chance of avoiding medication while still leaving all other options open.

What I hope you take away

If you've read this far, thank you for your patience. Let me summarise the key points:

Urgency and frequency are distinct from incontinence and deserve proper evaluation and treatment. You don't need to leak to merit help.

Pelvic floor physiotherapy is much more than "Kegels". It's a nuanced, evidence-based therapy that starts with assessment and may involve relaxation, strengthening, biofeedback, bladder retraining, or all of these—depending on what your body needs.

Half of people cannot correctly perform pelvic floor exercises after verbal instruction alone. Professional assessment ensures you're doing the right thing for your body.

All major guidelines recommend behavioural therapy as first-line treatment for overactive bladder—including "dry" OAB without incontinence.

Shame is a barrier to treatment. These are common, treatable conditions. The earlier you seek help, the easier it is to improve your quality of life.

If you're experiencing urgency, frequency, or other urinary symptoms, please speak to your GP or a specialist. In my practice, I start with a careful assessment and offer a treatment plan that may include behavioural therapy, pelvic floor physiotherapy and, if necessary, medication. The goal is always to find the approach that gives you the best outcome with the fewest downsides.

- Abrams P, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2002;21:167-178.

- EAU Guidelines on Non-neurogenic Female LUTS. European Association of Urology, 2024.

- NICE Guideline NG210. Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. 2021.

- AUA/SUFU Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Idiopathic Overactive Bladder. 2024.

- Bo K, et al. Is pelvic floor muscle training effective for symptoms of overactive bladder in women? A systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2020;106:65-76.

- Dumoulin C, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005654.

- Bump RC, et al. Assessment of Kegel pelvic muscle exercise performance after brief verbal instruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:322-329.

- Shafik A, Shafik IA. Overactive bladder inhibition in response to pelvic floor muscle exercises. World J Urol. 2003;20:374-377.

- Coyne KS, et al. The impact on health-related quality of life of stress, urge and mixed urinary incontinence. BJU Int. 2003;92:731-735.

- Pieper NT, et al. Anticholinergic drugs and incident dementia, mild cognitive impairment and cognitive decline. Age and Ageing. 2020;49:939-947.

NHS Resources

- NHS — Urinary Incontinence (Covers OAB & Urgency) https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-incontinence/

- NHS — Pelvic Floor Exercises (Women) https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/womens-health/what-are-pelvic-floor-exercises/

- NHS — Pelvic Floor Exercises (Men) https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/mens-health/what-are-pelvic-floor-exercises/

BAUS (British Association of Urological Surgeons)

- BAUS — Overactive Bladder (OAB) https://www.baus.org.uk/patients/conditions/13/overactive_bladder_oab

- BAUS — Pelvic Floor Exercises for Men (PDF Leaflet) https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Pelvic%20floor%20XS%20male.pdf

International Continence Society (ICS)

- ICS — Overactive Bladder (Fact Sheet) https://www.ics.org/public/factsheets/overactivebladder

- ICS — Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (Fact Sheet) https://www.ics.org/public/factsheets/pelvicfloormuscleexercises

IUGA (International Urogynecological Association)

- IUGA — Patient Leaflets Library (Includes specific PDFs for Overactive Bladder, Bladder Training, and Pelvic Floor Exercises) https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/leaflets/

NICE Guidelines (Patient Versions)

- NICE — Urinary Incontinence & Pelvic Organ Prolapse (NG123) (Replaces the outdated CG171) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123/informationforpublic

- NICE — Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (NG210) (Newer guidance from 2021) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng210/informationforpublic

Physiotherapy & Charity Sources

- Pelvic Obstetric & Gynaecological Physiotherapy (POGP) (Highly detailed booklets for both men and women) https://pogp.csp.org.uk/publications

- Bladder & Bowel UK — Adult Bladder Health https://www.bbuk.org.uk/adults/bladder/